The Dust of War

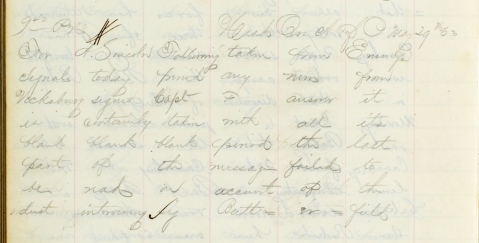

9:40 p.m. HeadQrs A of P May 29th 63

For A. Lincoln Following taken from Enemys

Signals today period any news from

Vicksburg signed Capt. F. answer

it is certainly taken with all its

blank blank blank period the last

part of the message failed to

be read on account of the

dust intervening Sig. Butt = er = field

The month of May of 1863 was a trying time for the president. If he hadn’t enough dealing with the fallout from the defeat at Chancellorsville, there was a feud between Samuel P. Curtis with the governor of Missouri, not to mention a constitutional crisis triggered by the arrest of Clement L. Vallandigham, the leader of the anti-war Democrats. The only bright spot was the reports from Ulysses S. Grant’s army: on May 18, Vicksburg, the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” was under siege. By the end of the month, however, Lincoln’s elation had given gave way to anxiety: there was no news of progress, and Grant appeared to be bogged down.

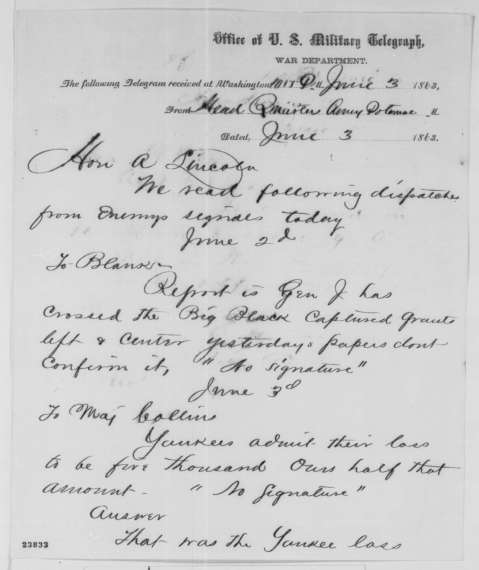

Daniel Butterfield, the chief of staff to the commander of the Army of the Potomac, supplied the anxious president with bits of intelligence gathered from the Confederate sources. On June 4, for example, he telegraphed a gleeful report from the Richmond Sentinel: “The federal troops are demoralized & refused to renew the attack on Saturday. The enemy’s Gunboats are firing hot shot at the City the federal loss is estimated at 25,000 or 30,000.” Lincoln dismissed this report.

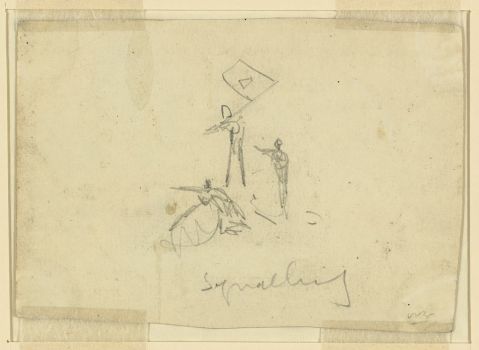

One of Butterfield’s main sources of information were intercepted wig-wag signals. This type of communication involved waving flags in a binary code similar to Morse’s system of dots and dashes.

Waud, Alfred R. (Alfred Rudolph), 1828-1891. Signaling. Paper , pencil. Morgan collection of Civil War drawings (Library of Congress); DRWG/US – Waud, no. 845 verso

The system had been developed in the 1850s, by Albert J. Myer who was appointed to lead the Union Army’s Signal Corps in March 1863. The Confederate Army beat the Union command: the Signal Corps headed by William Norris and attached to the Inspector General’s Department had been in operation since April 1862. Because the Confederates used a slightly modified Myer’s system, their intercepted messages could be deciphered without much difficulty.

The Confederate command relied on signal communications to a much greater degree than their Union counterparts, largely due shortages of telegraph wire and trained telegraph operators. Confederate signal men could be privy to valuable information. The Confederate Secret Service Bureau was folded into the Signal Corps , and thus intelligence gathering and covert operations fell under its aegis.

Butterfield’s men seemed to watch the enemy signal officers very closely, and Butterfield routinely telegraphed the findings to Washington. Apparently, the Confederate signal men not only provided tactical battlefield communications, but also transmitted news and even rumors. On 9:40 of June 3, for example, Butterfield reported that “Rebel signals yesterday say ‘Nothing new from Vicksburg.” Twelve hours later, news had moved on, as seen from this telegram (Papers of Abraham Lincoln at the Library of Congress; Series 1. General Correspondence, 1833-1916):

Our, previously unknown, telegram uncovered by our volunteers escholzia and S.Holm reveals that there were rumors to the contrary. This is probably why Butterfield felt compelled to convey a message, despite the fact its large chunk could not be read “on account of the dust intervening.”

This was not the first-time news of the Union victory popped up. Just five days before, Lincoln anxiously telegraphed to Anson Stager “Late last night Fuller the quartermaster telegraphed you, as you say, that “the stars and stripes float over Vicksburg, and the victory is complete.” Did he know what he said, or did he say it without knowing it?” Stager replied that the message that William G. Fuller, the telegraph superintendent for the Army of the Tennessee, was “no doubt based upon the hopeful feeling.”

So far, we don’t know how or whether Lincoln responded to Butterfield’s update. If refused to get his hopes up, he, of course, was right: Vicksburg would not be taken “with all its blank blank blank” until the Glorious Fourth of 1863.

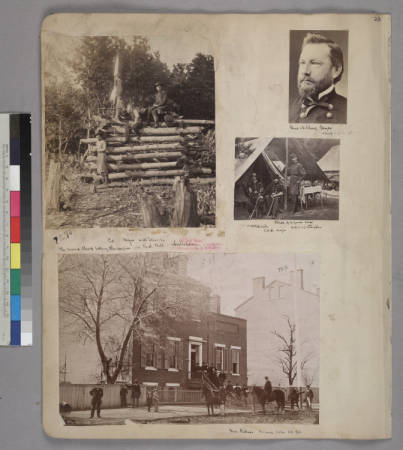

Chief of Signal Corps; Capt. L.B. Norton, Col. A.J. Myer, Capt. WS Stryker. James E. Taylor Collection. The Huntington Library.

Olga Tsapina, Norris Foundation Curator of American History, Huntington Library