Mechanics of Telegram Traffic, Getting from A to B

By Daniel Stowell, Director and Editor of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

In response to a query from one of our fantastic volunteers, crmiller211, and prodded by my colleagues Mario Einaudi and Kate Peck, I am going to explain the process of telegram traffic. I am focusing on how message X went from A to B the best I understand it, based on the research I did for the article (see p. 4-8) that walks through the process of decoding a telegram. In terms of actual mechanics, I fear I am no expert on the operation of the telegraph keys themselves. There are active historical reenactors of the United States Military Telegraph that might be able to address some of those issues.

Message going from A to B. Let’s start with Lincoln, as that’s my guy.

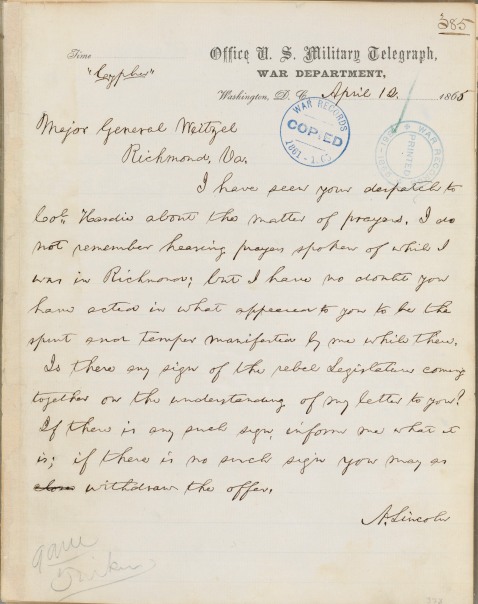

Lincoln writes out a telegram, sometimes on Executive Mansion stationery (1). If he wants it sent secretly, he writes “Cypher” at the top. Notoriously bad speller, that Lincoln. He gives it to Eckert or someone in the telegraph office or has it sent by trusted secretary to the War Department a block from the Executive Mansion.

Abraham Lincoln to Godfrey Weitzel, 12 April 1865, RG 107, Entry 34: Records of the Secretary of War, 1789-1889, Telegrams Sent and Received by the War Department Central Telegraph Office, 1861-1882, Vault, National Archives, Washington, DC.

A cipher telegrapher at the War Department takes Lincoln’s telegram and rewrites it in a grid form (2), perhaps substituting arbitraries as he (almost always men, although I know there were exceptions, but I don’t think at the War Department) does so. He also likely writes out a separate copy on a slip of paper in transmission order based on the route cipher used (3).

Telegram from Lincoln to Weitzel, in code, Thomas T. Eckert Papers, mssEC 18, p. 323, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

If you’re keeping count, that means that there are already three copies of the telegram in Washington.

A telegrapher sends the message, let’s say to General Weitzel in Richmond, Virginia. As I understand the process, the telegram may have to be intercepted and re-transmitted along the way, depending on the distance, but I’ll skip over that issue for now. My understanding is also that at least on some messages, the receiving telegrapher repeated back the message to the sender, either in sections or in its entirety to insure correct transmission.

In Richmond, a telegrapher writes down the letters/words as received (4). A cipher telegrapher then takes that sheet and arranges the words in a grid form according to the route cipher, perhaps substituting clear words for arbitraries as he does so (5). Then, the telegrapher writes out the message in a clear form for General Weitzel (6).

By my count, that’s at least six copies of the telegram between Lincoln and Weitzel at a minimum, three in Washington and three in Richmond. This total does not include the possibility of correspondence logs that at least some governors, generals, and others kept of all incoming and outgoing correspondence, which would add additional copies.

Finally, a few observations:

- An “ordinary” telegrapher could send or receive an encoded message, so long as he did not have access to the code books, but only a cipher telegrapher could encode and decode the messages. The number of such telegraphers was kept to a minimum by design.

- Neither Lincoln nor Weitzel would have known the exact nature of the cipher, though Lincoln certainly knew and requested that messages be sent in cipher, as did generals, governors, etc.

- My guess is that intermediate forms of telegrams were destroyed to cut down on clutter and prevent any “leaks” of information that Confederate agents could use to try to decode the cipher. In a camp setting, they were likely burned, and perhaps even in cities like Washington and Richmond they were burned as well. Severely restricting access to the code books was essential to the cipher’s success.

- If I am right about the above, it would explain the absence of many intermediate forms in the historical record. The transmission order telegram copy we have for the Lincoln-to-Weitzel telegram about which I wrote is quite rare, perhaps not destroyed because it came at the end of the war.

- My guess is that the Eckert telegram books are either:

- Texts 2 (sent) and 5 (received) in the scenario above; or

- Correspondence log copies of all telegrams that were sent and received that were entered in books, perhaps at the end of each day.

Thank you! You’ve answered a lot my question. It makes sense that these books could have been end-of-the-day copies for the record as they’re too neat to have been written in a panic and there only seems to be a few writers’ handwriting involved. What still intrigues me, tho, are the telegrams that ramble on and on…that had to be strategic somehow, especially as they had to be copied so many times. Were they maybe red herrings?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad that we answered some of your questions. As for some of the longer telegrams, many of these are reports of actions taken or ongoing. They were sent to Washington to keep all informed. A good example of this are the reports sent by Charles Dana, who was the representative of the civil authority in the military theater. His often lengthy and very detailed reports were highly prized by Secretary Stanton and President Lincoln. Whether the telegram operators held his reports with the same enthusiasm is probably lost in the mists of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks to everyone involved in the publishing of this informative blog post. It answers many questions concerning the creation and ultimate disposition of Union Civil War telegrams. It helps to flesh out and make the Decoding Project all the more fascinating.

LikeLiked by 2 people

These bound books of telegrams have to be copies made directly into the bound books for the purpose of preservation, by whom and when would be up in the air, no?

LikeLike